بِسۡمِ اللهِ الرَّحۡمٰنِ الرَّحِيۡمِ

Table of Contents

- Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Claim to be a Prophet?

- Were There Any “Ẓillī” Prophets Before Mirza Ghulam Ahmad?

- The Evolution of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s Claims: From Reformer to Prophet

- What is the Islamic Definition of a Prophet and Criteria for Prophethood?

- Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Criteria for Prophethood?

- Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Exhibit the Character of a Prophet?

- What is the Messiah in Islamic Eschatology?

- Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Requirements for Being the Messiah?

- What is the Mahdi in Islamic Eschatology?

- Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Requirements of the Mahdi?

- Are the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Within the Fold of Islam?

- Conclusion

Introduction

This article is the outcome of a personal effort to understand the beliefs of the Ahmadiyya community and to share those findings with others for the purposes of education. It should not be interpreted as an attempt to demonise anyone, nor as an invitation to debate or polemicise. Rather, it is a study motivated by curiosity, a desire for clarity, and a commitment to examining religious claims through recognised Islamic standards.

The focus of this article is Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s three foundational claims: to be a Prophet, the Promised Messiah, and the Imam Mahdi, evaluated through the lens of traditional Islamic scholarship to assess their legitimacy under Shariah. If adequate Shariah-based evidence for Prophethood cannot be established, an important question arises: what is the religious status of those who follow him, and why?

The establishment of a new Ahmadiyya place of worship in Huddersfield, which had its open day on 29th November 2025, prompted this personal inquiry into the claims of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908) of Qadian. Rather than relying on secondary or polemical sources, this exploration relies on primary material from both the Ahmadiyya community and mainstream Islamic scholarship, enabling readers to assess the evidence fairly and objectively.

The Ahmadiyya Movement diverges significantly from mainstream Islamic orthodoxy regarding Prophethood, eschatology (study of the end of times), and the finality of revelation. This article, therefore, examines Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s three claims systematically and logically in light of fourteen centuries of Islamic definitions, doctrinal criteria, and eschatological prophecies. While the scope is intentionally limited to these three claims, the research draws from the Qur’an, major hadith collections, classical commentaries, Ahmadiyya publications (particularly Al-Islam.org), mainstream theological works, and academic studies of modern Islamic movements. Those seeking an exhaustive treatment of the subject, particularly from a scholarly and historical perspective, are encouraged to consult the extensive literature available in Urdu.

I have elected to use the term "Ahmadiyya" to exclusively mean the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. This was the term Mirza Ghulam Ahmad adopted himself in a manifesto on 4th November, 1900.

Dr. A. Hussain,

Huddersfield, UK,

December, 2025

1. Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Claim to be a Prophet?

In brief, yes he did. In his book Haqiqa-tul-Wahi Mirza Ghulam Ahmad wrote, “I am a ẓillī nabī by virtue of perfect obedience to the Holy Prophet, and I have received his name, his reflection, and his prophethood.” In Ail Ghalati Ka Izala he wrote, “A zill is one who becomes so completely annihilated in his Prophet that he receives the Prophet’s name and qualities by reflection.”

The mainstream Ahmadiyya community affirms that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad claimed to be a ẓillī nabi which is translated as "subordinate prophet" or "shadow prophet" or "reflective prophet". Such a prophet is "non-law-bearing" (ghayr tashri‘i) and compatible with the finality of Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). They argue his role introduced no new law but functioned as a spiritual extension of Islam's completed prophetic mission.

). They argue his role introduced no new law but functioned as a spiritual extension of Islam's completed prophetic mission.

The Ahmadiyya community is not monolithic. The mainstream branch, established in 1889, considers acceptance of Mirza as Promised Messiah, Mahdi, and subordinate Prophet essential to faith. The Lahore branch interprets him as a mujaddid (reformer) rather than a Prophet in any technical sense, understanding the title metaphorically.

Central to mainstream Ahmadiyya theology is distinguishing independent, law-bearing Prophets (which ended with the Prophet Muhammad (![]() )) from subordinate, non-law-bearing Prophets (which they argue may still arise). Within this model, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is viewed as a spiritual successor deriving authority solely through the Prophet Muhammad (

)) from subordinate, non-law-bearing Prophets (which they argue may still arise). Within this model, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is viewed as a spiritual successor deriving authority solely through the Prophet Muhammad (![]() ).

).

2. Were There Any "Ẓillī” Prophets Before Mirza Ghulam Ahmad?

The concepts of ẓill ("shadow") and burūz ("spiritual manifestation") belong to Sufi vocabulary describing hierarchical spiritual relationships between saints and prophets. Classical authors used these terms metaphorically, never to categorise new prophets after Revelation.

The renowned Sufi master Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani described sainthood as Prophethood's "shadow," presenting a hierarchy without implying saints become prophets. Ibn 'Arabi and Ahmad Sirhindi similarly used burūz to describe how perfected souls manifest prophetic qualities symbolically, not juridically. These concepts explained mystical states, not prophetic office.

Islamic theology recognises law-bearing and non-law-bearing prophets (e.g., Prophet Musa and Prophet Harun (![]() )), but this applied to historical figures within the Qur'anic narrative, not to justify Prophets after Prophet Muhammad (

)), but this applied to historical figures within the Qur'anic narrative, not to justify Prophets after Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). The Ahmadiyya movement places Mirza Ghulam Ahmad within this framework, arguing his ẓillī Prophethood accords with established Sufi usage.

). The Ahmadiyya movement places Mirza Ghulam Ahmad within this framework, arguing his ẓillī Prophethood accords with established Sufi usage.

Mainstream scholarship argues Sufi concepts were never applied to establish new prophetic offices. No figure prior to Mirza claimed Prophethood on this basis after Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). If ẓillī Prophethood is legitimate, it would alter the doctrine of finality, opening theological space classical thought intentionally closed. The consensus across Sunni and Shia scholarship maintains that no Prophet, whether independent, subordinate, or reflective, can arise after Prophet Muhammad (

). If ẓillī Prophethood is legitimate, it would alter the doctrine of finality, opening theological space classical thought intentionally closed. The consensus across Sunni and Shia scholarship maintains that no Prophet, whether independent, subordinate, or reflective, can arise after Prophet Muhammad (![]() ).

).

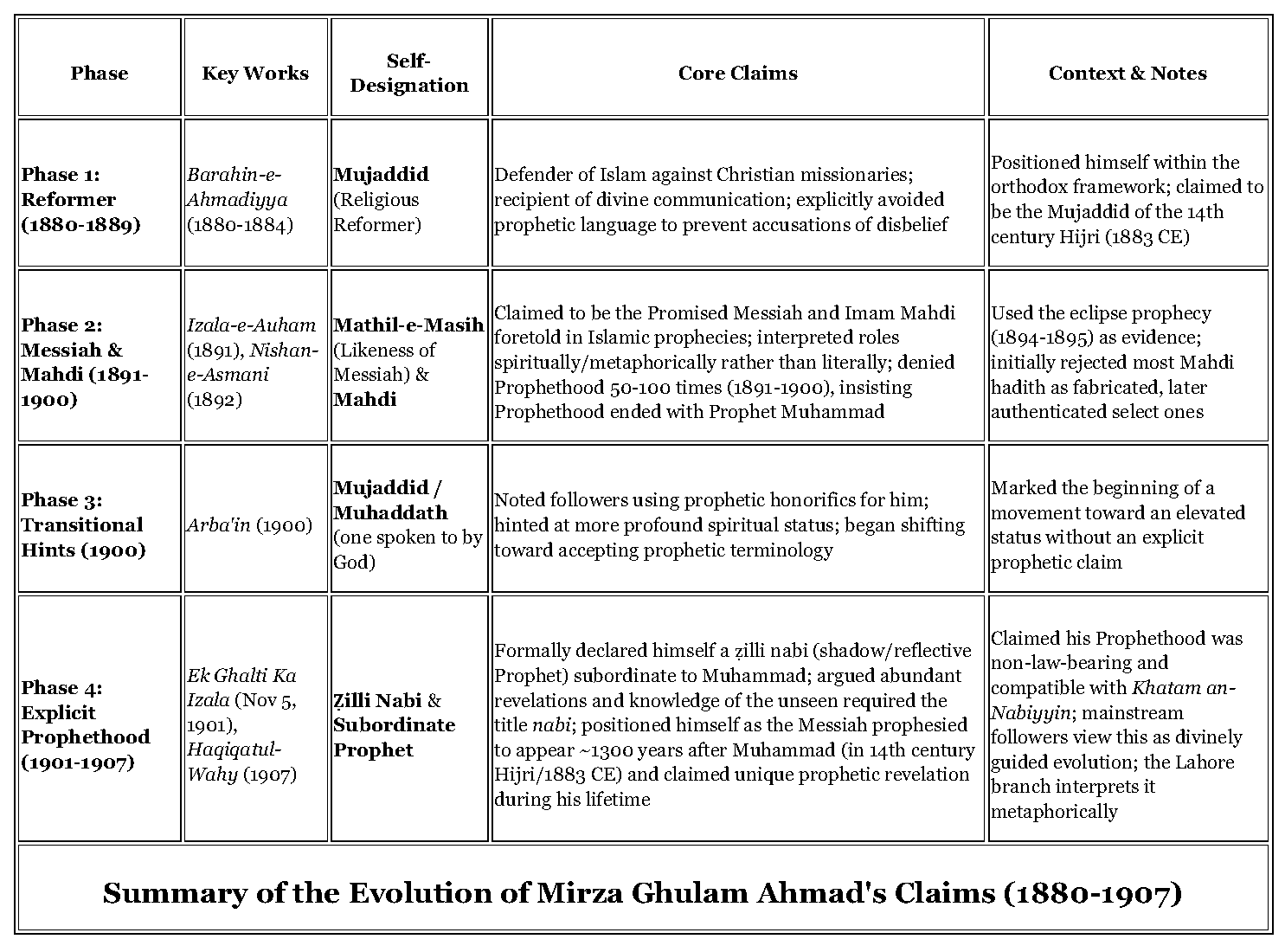

3. The Evolution of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s Claims: From Reformer to Prophet

Mirza's claims evolved dramatically over three decades. In the 1880s, particularly in Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya (1880-1884), he presented himself as a mujaddid (reformer), explicitly avoiding prophetic language to avoid charges of disbelief.

In 1891, with Izala-e-Auham, he identified himself as the Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi, interpreting these roles spiritually rather than literally. Between 1891-1900, he emphatically denied Prophethood 50-100 times, insisting Prophethood in the technical sense had ended with Prophet Muhammad (![]() ).

).

By 1900, subtle changes appeared. Works such as Arba'in indicate that followers began addressing him with prophetic honorifics. The decisive shift occurred in 1901, with Ek Ghalti Ka Izala (November 5, 1901), where he explicitly adopted the designation of ẓillī nabi (shadow Prophet), subordinate to Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). He would have been 66 years and 8 months at that time, to die 6 and half years later in May, 1908. He argued his abundant revelations, including knowledge of unseen matters, required the title nabi. In Haqiqatul-Wahy (1907), he positioned himself as the promised Messiah who was prophesied to appear approximately 1300 years after Prophet Muhammad (

). He would have been 66 years and 8 months at that time, to die 6 and half years later in May, 1908. He argued his abundant revelations, including knowledge of unseen matters, required the title nabi. In Haqiqatul-Wahy (1907), he positioned himself as the promised Messiah who was prophesied to appear approximately 1300 years after Prophet Muhammad (![]() ), and claimed to be uniquely receiving prophetic revelation (as a subordinate prophet) during his lifetime

), and claimed to be uniquely receiving prophetic revelation (as a subordinate prophet) during his lifetime

Critics argue documented denials contradict his later claims, questioning consistency and sincerity. His mainstream followers respond this represents divinely guided evolution, not reversal, maintaining his fundamental message, God's continued communication, remained constant. The Lahore branch interprets his prophetic terminology metaphorically, arguing his denials necessitate reading later language as spiritual resemblance rather than technical Prophethood.

4. What is the Islamic Definition of a Prophet and Criteria for Prophethood?

In Islamic belief, a nabi (Prophet) is chosen by God to receive divine revelation for guiding humanity. Prophets receive wahy, direct divine communication characterised by certainty, authority, and immunity from error, distinguishing them from saints who experience ilham (inspiration) but not revelation.

A fundamental sign of Prophethood is knowledge of the unseen (ghayb), ability to convey divine truths about future events, moral realities, and spiritual principles inaccessible through ordinary means. Prophets are divinely protected from major sin and safeguarded from error when conveying revelation ('ismah). They are moral examples whose lives embody the principles they teach, consistently affirming monotheism and calling communities to moral accountability.

The doctrine of Khatam an-Nabiyyin, that of Prophet Muhammad (![]() ) is the "Seal of the Prophets", is foundational. Across all major theological schools, this affirms the completion of the prophetic mission with Prophet Muhammad (

) is the "Seal of the Prophets", is foundational. Across all major theological schools, this affirms the completion of the prophetic mission with Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). His revelation is final, comprehensive, and universally binding, superseding all previous scriptures. Consequently, any new Prophet's emergence, whether independent or subordinate, is incompatible with mainstream Islamic thought. Finality functions as a foundational principle defining Islam's completeness and self-sufficiency.

). His revelation is final, comprehensive, and universally binding, superseding all previous scriptures. Consequently, any new Prophet's emergence, whether independent or subordinate, is incompatible with mainstream Islamic thought. Finality functions as a foundational principle defining Islam's completeness and self-sufficiency.

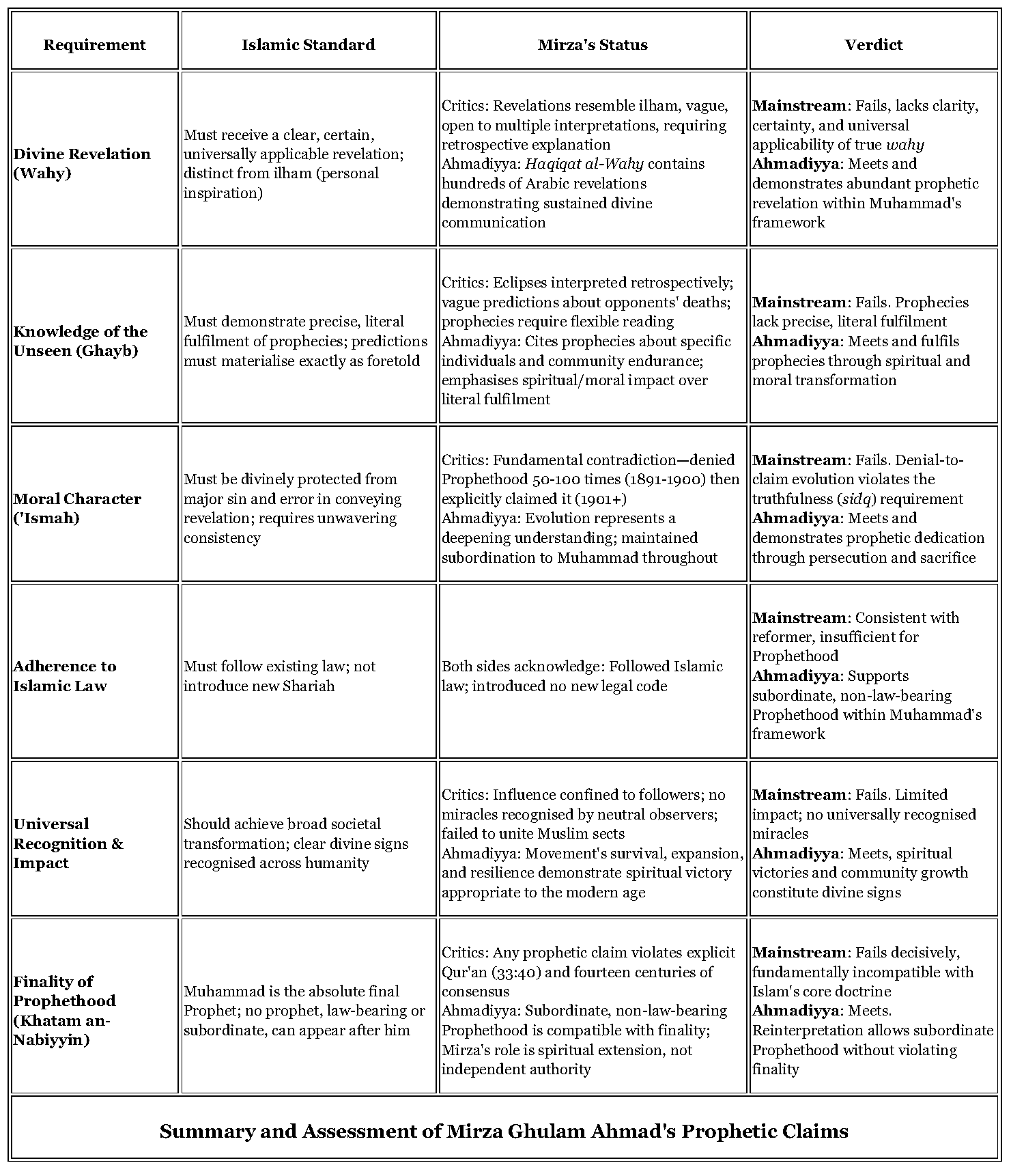

5. Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Criteria for Prophethood?

Mainstream Sunni and Shia scholarship maintains Mirza's claims don't meet Prophethood's historical standards, as his self-understanding and revelations diverge from the Islamic definition. The Ahmadiyya community maintains his role aligns with a specific, subordinate Prophethood compatible with Prophet Muhammad's (![]() ) finality.

) finality.

In terms of divine revelation, Islamic standard requires wahy, a clear, certain, universally applicable revelation. Critics argue Mirza's revelations resemble ilham (personal inspiration), pointing to vague statements open to multiple interpretations and prophecies requiring retrospective explanation. The Ahmadiyya community cites Haqiqat al-Wahy, arguing it contains hundreds of Arabic revelations demonstrating sustained divine communication.

Regarding knowledge of the unseen, critics note his prophecies, such as eclipses interpreted retrospectively and predictions about opponents' deaths as vague fulfilments which do not conform to precise, literal fulfilment expectations. Supporters cite prophecies concerning specific individuals and community endurance, interpreting them through spiritual and moral impact rather than immediate literal realization.

Both sides acknowledge Mirza followed existing Islamic law and introduced no new Shariah. Classical scholarship views this as consistent with a reformer; the Ahmadiyya interpret it as supporting subordinate, non-law-bearing Prophethood within Prophet Muhammad's (![]() ) framework.

) framework.

Mainstream Islamic scholars note his influence remained confined to followers without broader societal transformation. The Ahmadiyya community interprets their movement's survival and expansion as spiritual victory appropriate to the modern age.

These disagreements reflect broader theological frameworks. Mainstream scholars maintain his claims are fundamentally incompatible with prophetic finality. The Ahmadiyya Movement interprets criteria through a distinct hermeneutical lens, arguing he fulfilled a subordinate Prophet's role to revive, not replace, Islamic teachings.

6. Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Exhibit the Character of a Prophet?

Islamic scholarship emphasises Prophets embody exceptional moral standards: truthfulness, trustworthiness, sound judgment, humility, and protection from major error. Critics argue Mirza's life diverges from these expectations; his followers maintain he demonstrated precisely the qualities associated with a spiritual reformer endowed with prophetic responsibility.

Critics point to his 1891-1900 denials of Prophethood (50-100 instances), contrasting with his 1901+ prophetic claims. For those requiring unwavering consistency, this shift raises reliability questions. Supporters argue this reflects deepening self-understanding, with terminology evolving while the underlying mission, God's continued communication, remained constant. He consistently affirmed subordination to Prophet Muhammad (![]() ).

).

Critics argue that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad's participation in religious controversies, his evolving self-descriptions, and assertive tone, including the use of abusive and derogatory language to describe his Muslim opponents, appear inconsistent with prophetic conduct, while supporters view these interactions as part of his era's polemical landscape, maintaining that firmness in defending a divinely mandated mission does not contradict moral integrity. Both sides draw upon his perseverance, sacrifices, and commitment to preaching as evidence, critics questioning whether these qualities suffice for prophetic character, and supporters citing them as proof of his moral sincerity and dedication to reform.

7. What is the Messiah in Islamic Eschatology?

Mainstream Islamic eschatology (study of the end of times) identifies the Messiah (al-Masīḥ) exclusively as Prophet Jesus (![]() )(ʿIsa ibn Maryam), not a symbolic reformer. Classical tradition maintains Jesus (

)(ʿIsa ibn Maryam), not a symbolic reformer. Classical tradition maintains Jesus (![]() ) was neither crucified nor killed but raised bodily to heaven, where he lives until his return near the end of time. This expectation forms a consistent element in the hadith corpus, affirmed by scholars across Sunni and Shia schools.

) was neither crucified nor killed but raised bodily to heaven, where he lives until his return near the end of time. This expectation forms a consistent element in the hadith corpus, affirmed by scholars across Sunni and Shia schools.

His return is described in vivid, physical terms as descending from heaven near a white minaret in eastern Damascus, appearing in saffron-dyed garments, with a serene, humble demeanour. The imagery of droplets falling from his head like pearls is interpreted literally, reflecting belief that he returns in the same physical form in which he was raised.

A central feature is defeating the Dajjāl (Antichrist), described as the greatest trial humanity will face. The Dajjāl performs extraordinary feats, claims divinity, and misleads vast segments of humanity. When encountering Jesus (![]() ), his power collapses; he cannot withstand the Messiah's presence and is killed at the Gate of Lod near Jerusalem. This marks the end of extraordinary tribulation and begins a new era characterized by justice and spiritual clarity.

), his power collapses; he cannot withstand the Messiah's presence and is killed at the Gate of Lod near Jerusalem. This marks the end of extraordinary tribulation and begins a new era characterized by justice and spiritual clarity.

Following this, Jesus (![]() ) restores his original message, correcting misunderstandings that developed after his departure. This includes rejecting doctrines like the Trinity and affirming pure monotheism. Sources describe a period of unprecedented peace and harmony where Jesus plays a guiding spiritual role while the Mahdi serves as political leader. The symbolism of Jesus praying behind the Mahdi signifies respect for the finality of Prophet Muhammad's (

) restores his original message, correcting misunderstandings that developed after his departure. This includes rejecting doctrines like the Trinity and affirming pure monotheism. Sources describe a period of unprecedented peace and harmony where Jesus plays a guiding spiritual role while the Mahdi serves as political leader. The symbolism of Jesus praying behind the Mahdi signifies respect for the finality of Prophet Muhammad's (![]() ) law and unity under an established Islamic order.

) law and unity under an established Islamic order.

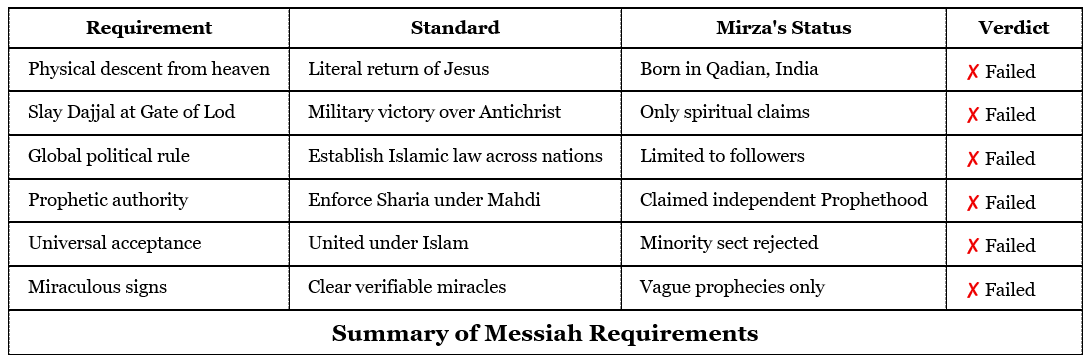

8. Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Requirements for Being the Messiah?

Mainstream Islamic thought defines the Messiah with considerable clarity, forming the basis for evaluating Mirza Ghulam Ahmad's claims. Traditional Qur'anic and hadith interpretations understand the Messiah as Prophet Jesus (![]() ). Mainstream scholarship maintains Mirza's self-understanding doesn't align with established messianic criteria, and the divergences are too substantial to reconcile.

). Mainstream scholarship maintains Mirza's self-understanding doesn't align with established messianic criteria, and the divergences are too substantial to reconcile.

Classical sources present the Messiah as Jesus (![]() ) returning in physical form, descending from heaven during global turmoil. However, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad taught Jesus died naturally in Kashmir centuries earlier and that return prophecies should be fulfilled spiritually rather than literally. This conflicts with scriptural passages and hadith describing Jesus's ascension and return in concrete terms.

) returning in physical form, descending from heaven during global turmoil. However, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad taught Jesus died naturally in Kashmir centuries earlier and that return prophecies should be fulfilled spiritually rather than literally. This conflicts with scriptural passages and hadith describing Jesus's ascension and return in concrete terms.

Hadith literature portrays Jesus (![]() ) physically defeating Dajjāl at the Gate of Lod. Mirza interpreted Dajjāl symbolically as religious and intellectual falsehood, particularly Christian missionary activity, regarding his writings and debates as fulfilling this role. This spiritual approach doesn't correspond to classical sources' detailed, literal descriptions, which present Dajjāl as an identifiable individual with detailed characteristics rather than an abstract force.

) physically defeating Dajjāl at the Gate of Lod. Mirza interpreted Dajjāl symbolically as religious and intellectual falsehood, particularly Christian missionary activity, regarding his writings and debates as fulfilling this role. This spiritual approach doesn't correspond to classical sources' detailed, literal descriptions, which present Dajjāl as an identifiable individual with detailed characteristics rather than an abstract force.

Traditional Islamic eschatology (study of the end of times) describes the Messiah presiding over universal justice, social harmony, and religious clarity, often with the Mahdi. These expectations include political authority and unifying diverse communities under restored monotheism. Mirza's circumstances differed markedly. He didn't exercise political power or claim governance roles. His influence was primarily spiritual and pastoral within his community.

Islamic tradition maintains the Messiah, upon returning, doesn't bring new revelation or independent authority but functions within Prophet Muhammad's (![]() ) framework. Mirza understood his mission to involve Prophethood that, while subordinate, entailed divine communication and elevated spiritual status. Mainstream scholars argue this represents departure from the classical distinction between Jesus's (

) framework. Mirza understood his mission to involve Prophethood that, while subordinate, entailed divine communication and elevated spiritual status. Mainstream scholars argue this represents departure from the classical distinction between Jesus's (![]() ) eschatological role and Prophethood's closure with Prophet Muhammad (

) eschatological role and Prophethood's closure with Prophet Muhammad (![]() ).

).

Classical Islamic literature portrays the Messiah's arrival leading to widespread monotheism acceptance across populations. Mirza's mission resulted in establishing a distinct community whose theological positions set it apart from mainstream Islamic interpretations. While the Ahmadiyya community views its cohesion, growth, and resilience as divine favour indicators, mainstream scholars regard a separate movement's emergence as inconsistent with the Messiah's unifying traditional role.

These differences reflect deeper theological interpretation, eschatological expectation, and religious authority understanding divergences. Mainstream Islamic scholars generally conclude Mirza Ghulam Ahmad's claims don't correspond to classical Messiah descriptions. The Ahmadiyya community interprets these descriptions through a symbolic or spiritual framework they believe accords with modern needs. The debate centres on fundamentally different approaches to interpreting the Messiah's nature and mission.

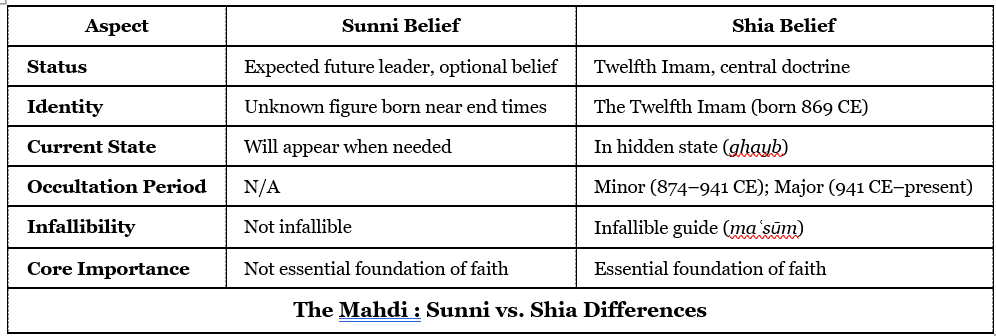

9. What is The Mahdi in Islamic Eschatology?

The Mahdi ("The Guided One") occupies a central place as the divinely guided leader destined to appear near the end of time in response to a world overwhelmed by injustice and moral collapse. His role is restoring righteousness, re-establishing Islamic law, and inaugurating an era of global justice.

Classical sources describe the Mahdi as a descendant of Prophet Muhammad (![]() ) through Fatimah's lineage. Sunni traditions specify that his name will correspond to the Prophet's own name, and his father's name will be 'Abd Allāh. His physical appearance resembles the Prophet Muhammad (

) through Fatimah's lineage. Sunni traditions specify that his name will correspond to the Prophet's own name, and his father's name will be 'Abd Allāh. His physical appearance resembles the Prophet Muhammad (![]() ), signalling lineage and spiritual continuity.

), signalling lineage and spiritual continuity.

The Mahdi's authority is political and spiritual. His rule of 7-9 years marks the revival of the Prophet's Sunnah and Islamic law after a long decline. He doesn't function as a prophet nor introduce new revelation, but as a righteous leader whose insight guides him in restoring religion to its original clarity. His mission centres on confronting oppression, spreading justice globally, and bringing profound spiritual transformation among Muslims and non-Muslims.

A defining element concerns his relationship with Prophet Jesus (![]() ) upon Jesus's (

) upon Jesus's (![]() ) return. While both appear during the same eschatological period, sources make clear that leadership resides with the Mahdi. Jesus's act of praying behind him symbolises Islamic dispensation supremacy and subordination of even a returning Prophet to the established Islamic order. This moment affirms Muhammad's (

) return. While both appear during the same eschatological period, sources make clear that leadership resides with the Mahdi. Jesus's act of praying behind him symbolises Islamic dispensation supremacy and subordination of even a returning Prophet to the established Islamic order. This moment affirms Muhammad's (![]() ) Prophethood finality and indicates Jesus's (

) Prophethood finality and indicates Jesus's (![]() ) end-times mission supports the Mahdi's leadership, particularly in defeating Dajjāl and establishing justice.

) end-times mission supports the Mahdi's leadership, particularly in defeating Dajjāl and establishing justice.

Islamic narratives describe world conditions preceding the Mahdi's emergence: widespread moral decay, abandonment of religious knowledge, Qur'anic teachings' erosion, natural disasters, political chaos, and corrupt figures' rise such as the Sufyani. These crises serve as signs alerting humanity that the final age has arrived. His appearance marks a decisive turning point, restoring spiritual order after severe disorder.

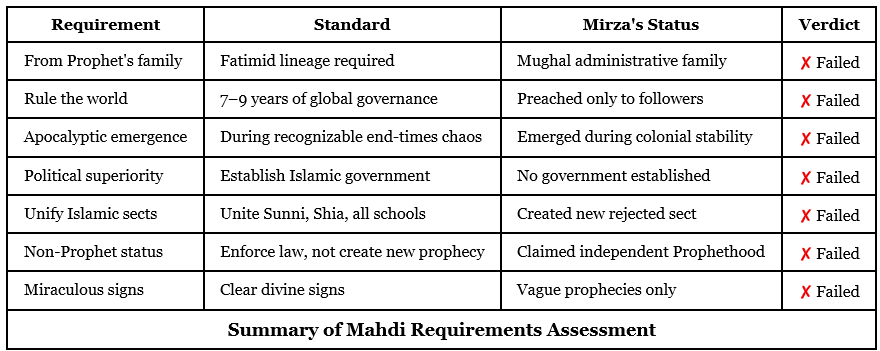

10. Did Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Fulfil the Requirements of the Mahdi?

Mainstream Islamic eschatology assigns the Mahdi precise genealogical, political, and historical expectations. Traditional teachings consistently maintain the Mahdi must descend directly from Prophet Muhammad (![]() ) through Fatimah, bearing the Prophet's name and his father's name. Mirza was born in 1835 in Qadian to a Mughal administrative family with no recognised lineage tracing to the Prophet's household. For classical scholars, this alone suffices to remove him from consideration, as lineage is not symbolic but a defining, indispensable requirement.

) through Fatimah, bearing the Prophet's name and his father's name. Mirza was born in 1835 in Qadian to a Mughal administrative family with no recognised lineage tracing to the Prophet's household. For classical scholars, this alone suffices to remove him from consideration, as lineage is not symbolic but a defining, indispensable requirement.

Islamic sources depict the Mahdi as a political and spiritual leader whose governance encompasses the world, instituting justice across nations and re-establishing Islamic law after centuries of decline. Mirza's activities were confined to religious leadership within his community; he neither ruled territory nor exercised political authority beyond his followers. His life unfolded entirely under British colonial rule, and he never pursued or achieved visible dominion associated with the Mahdi's mission.

The context of his emergence also differs markedly. Islamic eschatology situates the Mahdi within unmistakable global turmoil such as earthquakes, wars, plagues, celestial disruptions. Mirza announced his claims during relative colonial stability without dramatic upheavals described in prophetic texts. His interpretation emphasized spiritual fulfilment rather than apocalyptic transformation, diverging from literal descriptions traditionally shaping Muslim end-times expectations.

Moreover, Islamic traditions clearly distinguish between the Mahdi and Prophet Jesus (![]() ) after Jesus's (

) after Jesus's (![]() ) return. In the classical hierarchy, Jesus (

) return. In the classical hierarchy, Jesus (![]() ) descends from heaven and prays behind the Mahdi, affirming the Mahdi's role as final era's political leader. By merging Messiah and Mahdi roles or presenting himself in a Prophetic capacity differing from this structure, Mirza reinterpreted an arrangement Islamic tradition treats as fixed. His formulation collapsed roles classical eschatology keeps distinct.

) descends from heaven and prays behind the Mahdi, affirming the Mahdi's role as final era's political leader. By merging Messiah and Mahdi roles or presenting himself in a Prophetic capacity differing from this structure, Mirza reinterpreted an arrangement Islamic tradition treats as fixed. His formulation collapsed roles classical eschatology keeps distinct.

Underlying these differences is the theological issue of Prophethood. Islamic consensus holds that the Mahdi is not a Prophet and cannot be one, for no Prophet comes after Prophet Muhammad (![]() ). Mirza's Prophethood claim, regardless of qualification, stands in tension with this principle. By asserting Prophetic authority, he moved beyond bounds traditionally assigned to the Mahdi and introduced a doctrinal position mainstream scholars regard as incompatible with Prophethood's finality.

). Mirza's Prophethood claim, regardless of qualification, stands in tension with this principle. By asserting Prophetic authority, he moved beyond bounds traditionally assigned to the Mahdi and introduced a doctrinal position mainstream scholars regard as incompatible with Prophethood's finality.

The unity question is equally significant. Islamic sources portray the Mahdi as unifying divergent Muslim communities under restored, harmonised religious practice. Mirza's claim resulted in forming a new religious movement rejected across Sunni, Shia, and other Islamic schools. Rather than resolving fragmentation, his emergence added another layer to an already complex communal identity landscape.

Furthermore, signs associated with the Mahdi's recognition and acknowledgement by the broader Muslim community and clear, unmistakable prophecy fulfilment were absent in Mirza's case. His recognition remained limited to followers; mainstream Islam never accepted him as fulfilling expected eschatological conditions. Similarly, the Mahdi's task of restoring global Islamic governance, establishing the Sunnah and implementing Sharia across nations, was not undertaken during Mirza's lifetime. He lived under colonial authority, made no attempt to establish Islamic political rule, and his followers today continue living within secular legal frameworks.

For these reasons, mainstream Islamic scholarship holds Mirza Ghulam Ahmad's claim doesn't align with the traditional Mahdi understanding. His movement interprets the Mahdi's role in metaphorical and spiritual terms suited to a modern, non-political age, whereas classical sources insist the Mahdi's mission involves real political authority, visible transformation, and literal eschatological prophecy fulfilment. This fundamental divergence in method and expectation shapes the enduring difference between Ahmadiyya Movement’s interpretations and mainstream Islamic views.

11. Are the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Within the Fold of Islam?

Mainstream Islamic scholarship across Sunni and Shia traditions maintains that Ahmadiyya theology places the community outside Islam's established boundaries. This judgment primarily stems from accepting Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as a Prophet in some form, seen as conflicting with the classical interpretation of the Qur'anic declaration that Prophet Muhammad (![]() ) is the final Prophet. For mainstream scholars, even subordinate or metaphorical Prophethood represents departure from a definitive, non-negotiable doctrine.

) is the final Prophet. For mainstream scholars, even subordinate or metaphorical Prophethood represents departure from a definitive, non-negotiable doctrine.

Theological divergence extends beyond Prophethood to key eschatological concepts. Traditional scholarship, drawing on Qur'anic verses and mass-transmitted hadith, upholds literal understanding of Jesus's (![]() ) return, Dajjāl's emergence, and Mahdi's political leadership. The Ahmadiyya Movement reinterprets these symbolically or spiritually, suggesting Mirza fulfilled these roles through moral, intellectual, and spiritual renewal rather than literal events. This methodological shift reflects broader hermeneutic differences in approaching scriptural texts. Mainstream jurists generally contend such reinterpretations lack textual justification, especially when classical authorities understood these teachings in consistently literal terms for centuries.

) return, Dajjāl's emergence, and Mahdi's political leadership. The Ahmadiyya Movement reinterprets these symbolically or spiritually, suggesting Mirza fulfilled these roles through moral, intellectual, and spiritual renewal rather than literal events. This methodological shift reflects broader hermeneutic differences in approaching scriptural texts. Mainstream jurists generally contend such reinterpretations lack textual justification, especially when classical authorities understood these teachings in consistently literal terms for centuries.

These divergences have led major Islamic institutions, such as Al-Azhar and various national fatwa councils, to issue formal statements excluding the Ahmadiyya community from Islam's fold. Such rulings have informed legal interpretations in several Muslim-majority contexts, where Ahmadiyya community may face restrictions in marriage, inheritance, religious leadership, and participation in certain rites. These practical implications reflect the degree to which theological definitions shape legal and communal boundaries where Islamic law influences public policy.

The Ahmadiyya community maintains their adherence to the Five Pillars, Qur'an affirmation as divine revelation, and reverence for Prophet Muhammad (![]() ) as final law-bearing prophet place them firmly within the Islamic tradition. They cite concepts such as muhaddathiyyah, figures receiving divine inspiration, as precedent for understanding Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s role. They argue his mission continues the broader Islamic pattern of spiritual reform, which historically included individuals revitalising religious understanding during decline.

) as final law-bearing prophet place them firmly within the Islamic tradition. They cite concepts such as muhaddathiyyah, figures receiving divine inspiration, as precedent for understanding Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s role. They argue his mission continues the broader Islamic pattern of spiritual reform, which historically included individuals revitalising religious understanding during decline.

The Lahore branch attempts bridging the divide by interpreting Mirza as a mujaddid rather than a Prophet in any technical sense. This position rejects literal Prophethood while recognising his spiritual and intellectual contributions. However, even this moderated stance is not widely accepted in mainstream scholarship, largely because it continues placing Mirza at religious interpretation's centre in ways seen as redefining established doctrinal boundaries.

These disagreements' broader implications are evident in communal and religious life. In many Muslim societies, the Ahmadiyya community maintain separate worship places, religious institutions, and educational structures, reflecting theological separation's practical manifestation. Mainstream communities frequently do not recognise their religious ceremonies or leadership roles, as these are closely tied to doctrinal legitimacy within Islamic law.

Ultimately, whether the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad are Muslims depends on criteria adopted for defining Islamic identity. From the mainstream perspective, adherence to classical prophetic finality understanding forms a non-negotiable boundary. From the Ahmadiyya perspective, their interpretive approach preserves Islamic continuity while offering expanded spiritual renewal understanding. These positions remain fundamentally irreconcilable. As long as the Ahmadiyya community maintains belief in Mirza's Prophethood in any sense, mainstream Islamic authorities will not alter their position. Conversely, abandoning this belief would undermine the Ahmadiyya community identity's central conviction. The result is a theological divide reflecting not merely differing interpretations within Islam, but contrasting conceptions of its essential structure and religious authority nature.

12. Conclusion

After examining Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s three central claims through the lens of fourteen centuries of Islamic scholarship, it becomes evident that when Shariah, the very standard of evidence both sides claim to uphold, is applied consistently, the burden of proof lies squarely on Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and his followers to present conclusive Shariah-based evidence for his Prophethood, Messiahship, and Mahdiship. However, the primary sources, theological definitions, historical expectations, and doctrinal criteria established by classical scholars clearly show that his claims fail to meet the recognised Shariah requirements for any of these roles.

Beyond these Islamic titles, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad further expanded his theological scope by presenting himself as a Universal Reformer, claiming to be the Messiah for the Christians, the Second Coming of Krishna for Hindus, the Mesio-Darbahmi (Zoroastrian's Messiah) as well as Khatam al-Khulafa (Seal of the Khulafa ). He asserted that he was the spiritual manifestation (burūz) of all prior prophets, effectively combining the identities of figures like Adam, Abraham, and Moses (![]() ) into his own person. While intended to unify diverse faiths, these sweeping claims of universal convergence further deepened the theological rift with orthodox Islam, which regards such religious amalgamation as incompatible with the distinct eschatological function of the Messiah in Islam.

) into his own person. While intended to unify diverse faiths, these sweeping claims of universal convergence further deepened the theological rift with orthodox Islam, which regards such religious amalgamation as incompatible with the distinct eschatological function of the Messiah in Islam.

As a result, the doctrines affirmed by the Ahmadiyya community remain fundamentally incompatible with the core beliefs and boundaries that define Islam. Ultimately, the divide between the Ahmadiyya Movement and mainstream Islam rests on a foundational theological issue: the finality of Prophethood. This principle represents a firm and non-negotiable boundary of Islamic belief, one that cannot be altered or expanded by reinterpreting Sufi terminology of being zill (shadow) of the Prophet to being an actual Prophet, even if termed a ẓillī Prophet.

Dr. A. Hussain, Huddersfield, UK, Dec. 2025